#1: Magic Beans

Nigeria's surprising food delivery growth... & what it means for digital maturity

Welcome to foodpod, a limited series about technology eating food in Africa. Chapter 1 asks: can you build a business selling convenience in a market where money is more precious than time? Nigeria provides some revealing answers.

-

I’m often reminded of British science fiction writer Arthur Clarke’s third law (1968): “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” How else would you describe the fact that I can tap the pane of glass in my hand, and atoms miles away will deliver my plate of jollof? My ancestors would have cooked up some fascinating explanations.

The African technology ecosystem has invested billions of dollars and millions of hours to transform the continent using magic. Africa has many problems; some, of its own making. But one reason for optimism in the past decade has been that you can start solving them with technology. In a country like Nigeria, code and connectivity have made money weightless, transforming how we live and trade. Perhaps most intriguing is the transformation of a market as old as history itself.

Software has eaten communications, payments, credit, transportation, commerce, and a host of other sectors on the continent. And now, software is eating food:

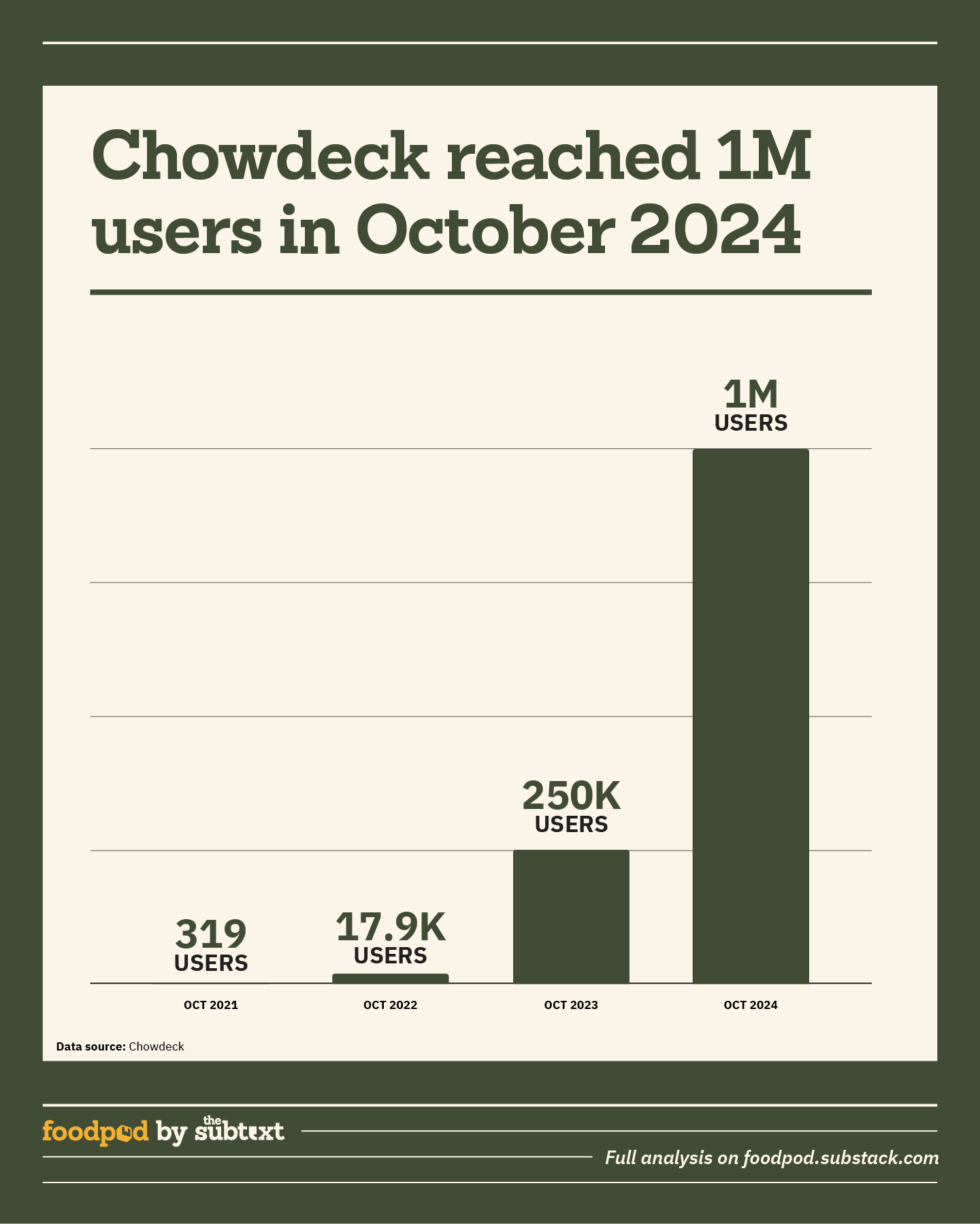

Something feels different about food delivery in Nigeria. And it's not just the numbers—though they are striking. Between 2021 and 2024, the sector grew at a compound annual growth rate of 187%, according to Paystack, which processes payments for all the major players in the space. The COVID pandemic created the conditions necessary for people and businesses to integrate delivery into their lives for the first time. This kicked off a Cambrian explosion, and in mere months, the Lagos landscape was filled with delivery couriers.

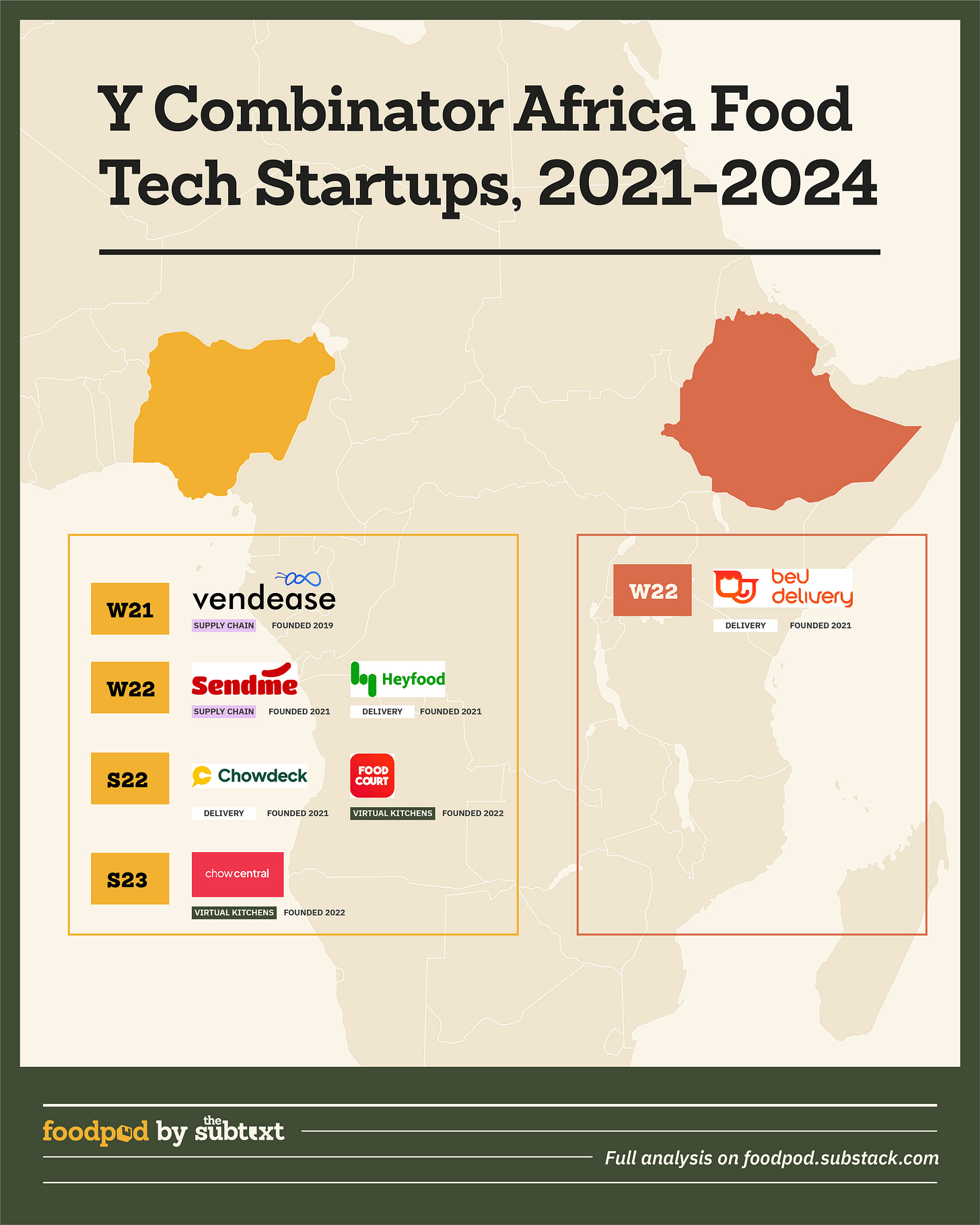

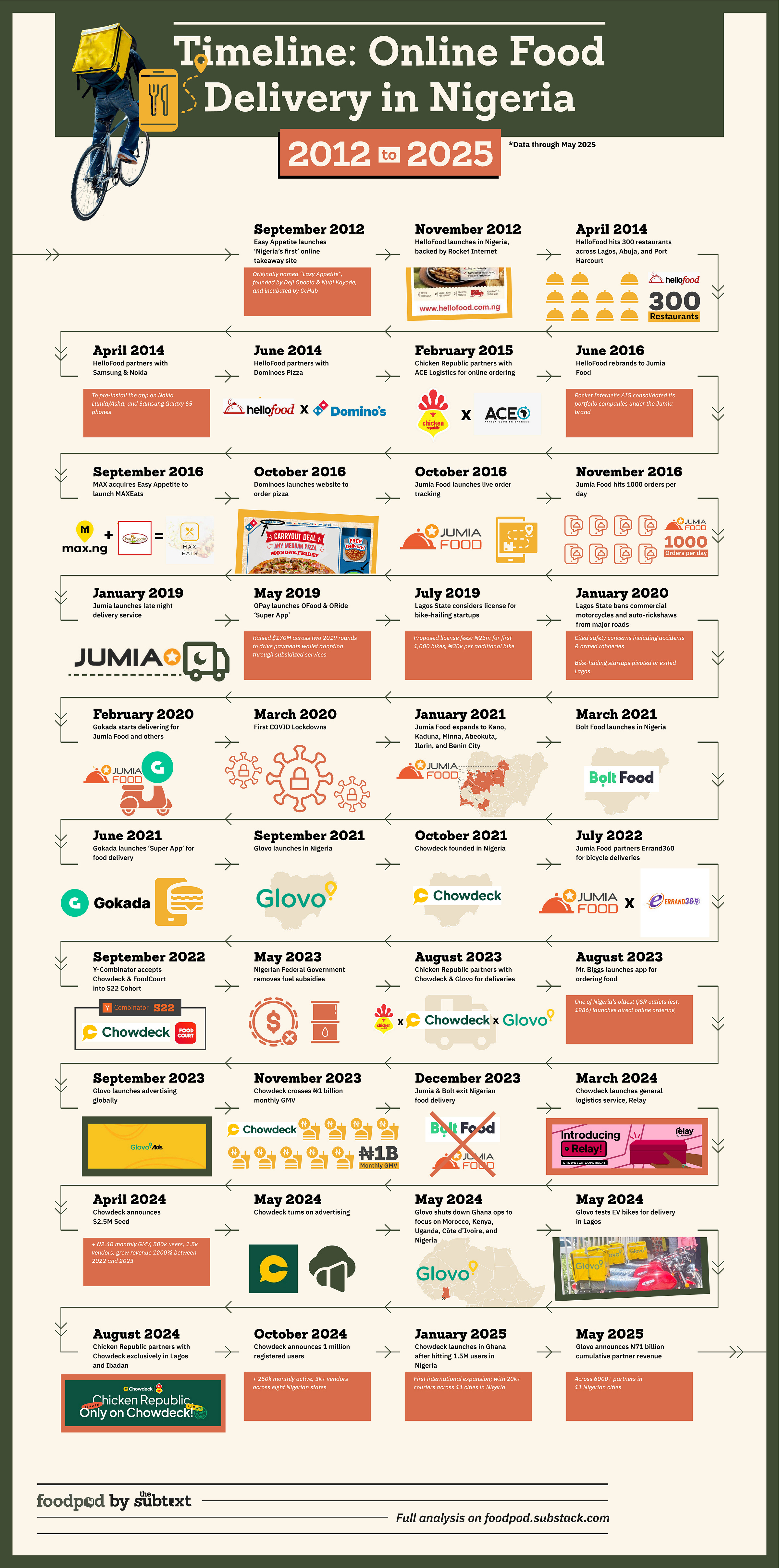

Bolt launched food delivery in Nigeria in March 2021, after raising $206M from D1 Capital Partners, Darsana, and the IFC. The Estonian ride-hailing company joined Jumia Food, which operated since 2012 but struggled with profitability; and Gokada, which pivoted to deliveries after the Lagos State motorcycle taxi ban. By September, Glovo entered the ring. The Spanish multi-category delivery app scaled successfully in Morocco, Kenya, and Cote d'Ivoire; the ‘Giant of Africa’ was next on the menu. Chowdeck emerged a month later, finding its initial audience among local bukas and cloud kitchens. FoodCourt, Chowcentral, Heyfood, GoLemon, MANO, Shoppr, Dropper, and many more entered the market with variations of the same basic promise: fast or convenient delivery.

What began as a niche service is now supported by deepening infrastructure. Jumia Food once served three major cities in Nigeria with just 80 couriers; today, Chowdeck alone has over twenty thousand, making more than forty thousand deliveries per day.

What makes this growth fascinating is the fact that Nigerians have lost over half their purchasing power in the last three years1. Basic items like rice, sachet water, Gala, and petrol have all quadrupled in price. With the naira in freefall, and living costs growing out of reach, there should be no money left over for ‘frivolities’ like delivery. And yet, today, more Nigerians than ever are choosing to order food online:

—

Everybody needs to eat. They’ll eat regardless of economic condition or social context; it is more a question of what to eat or how to buy. The choice to order online says something about a customer–their access to digital payments, willingness to trust internet services, and maybe even disposable income. This makes delivery2 a good barometer for internet ecosystem maturity in a given market.

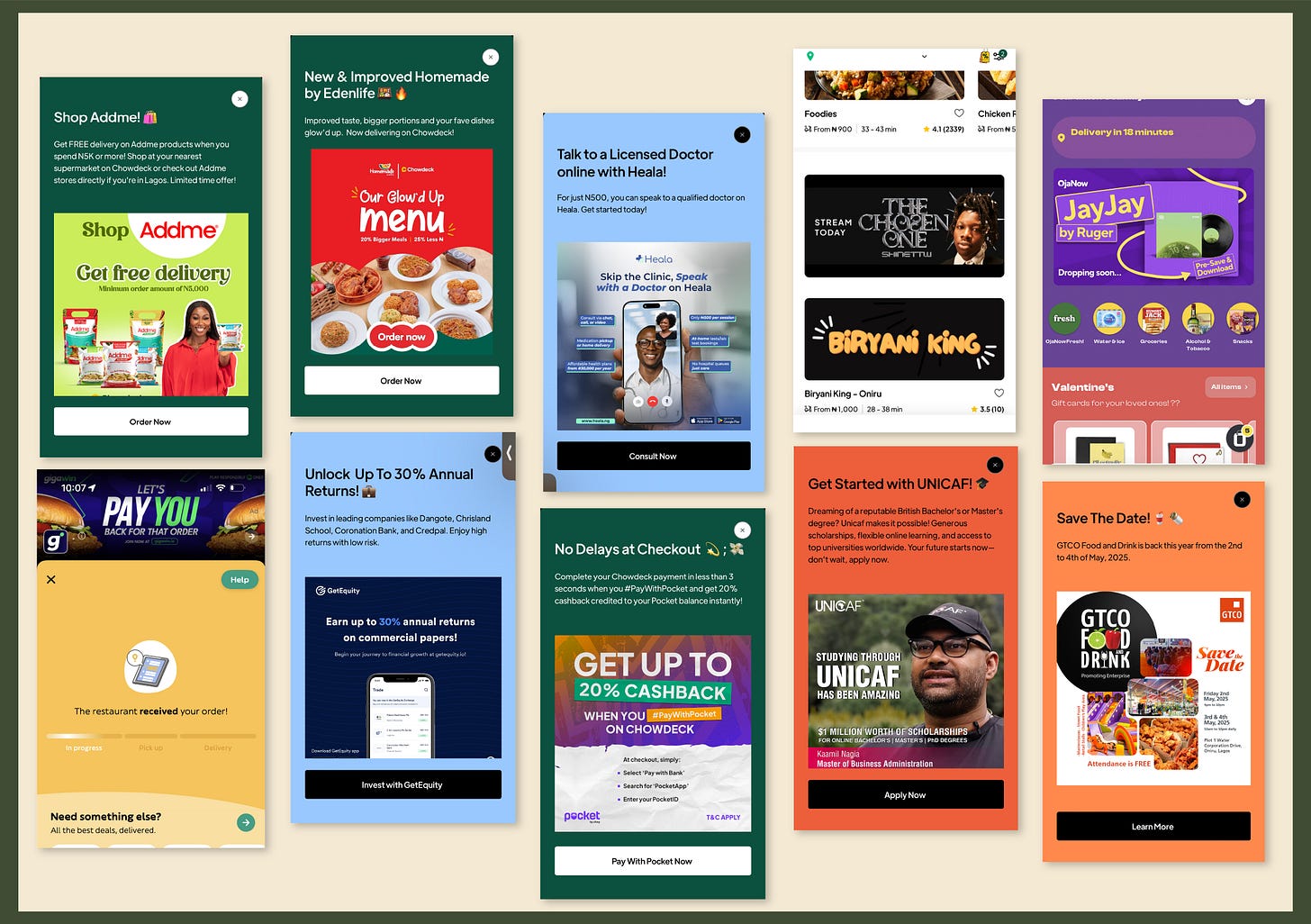

In Nigeria, food delivery has transformed from a niche service to a cultural phenomenon. Where delivery platforms once struggled to capture user attention, today, they have become marketing channels in their own right. Music labels, fintechs, banks, and even consumer goods brands compete for placement alongside burgers and shawarmas. This tells me something’s changed about the depth of demand for digital services in the country.

Beyond consumer culture, food delivery also serves as a window into seller behavior. When merchants begin selling online, they’re often taking their first steps towards digital transformation.

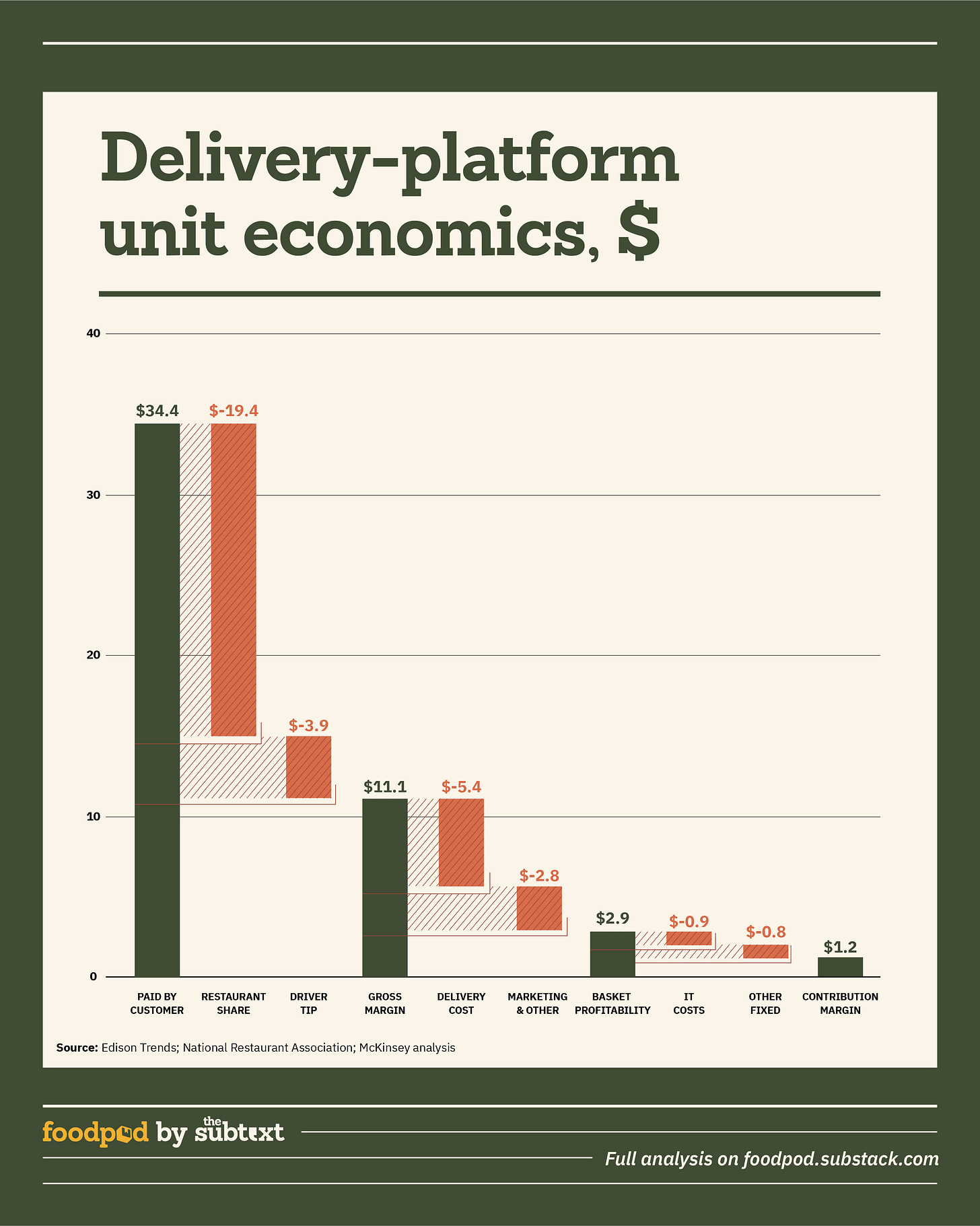

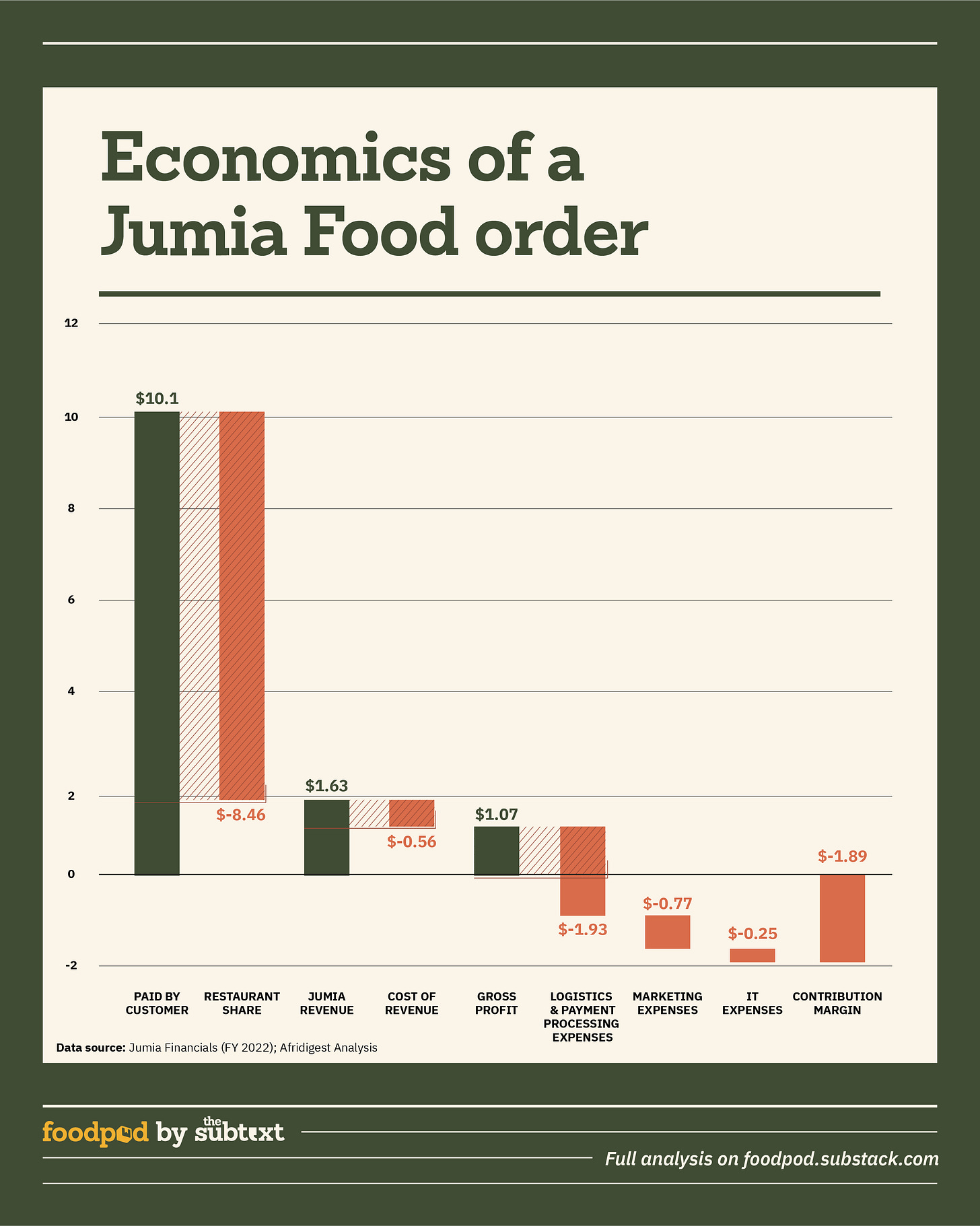

The promise of food delivery is that a restaurant can maximize the value from its kitchen by serving as many people as possible–many more than the dining area can take. Delivery platforms write software to generate demand, handle payments, and facilitate the final delivery. For their trouble, they take a fee on each order, typically 20-30%.

But moving atoms also means incurring operational costs: restaurants, riders, agents/support staff, who must be paid to facilitate each transaction. These costs compound at scale, producing razor-thin margins that erode with each level of growth. It’s often a matter of time before the company collapses under its own weight.

Jumia and Bolt exited Nigerian food delivery3 in 2023, citing ‘challenging market dynamics’ and rising operational costs. They’re hardly alone–the history of digital logistics is littered with well-funded casualties.

So, what is true? Has the market fundamentally changed? Will the new entrants make it to scale? Or will they follow their predecessors and flame out in a few years?

Can you build a business selling convenience in a market where money is more precious than time?

**

Takeout & Delivery: An Incomplete History

While we often think about delivery as a modern phenomenon, humanity’s desire for convenience has a long history. When people gather into clusters–typically around economic/administrative activity—they specialize. Inevitably, some will choose to spend time on other things, rather than cooking their own food.

Since the earliest urbanization, getting food from where it's prepared to where it's consumed has been a fundamental economic activity:

In Ancient Rome, working class people bought hot takeout meals from thermapolia (cook shops) in major cities like Pompeii. If you squint, these were the first quick service restaurants.

During South Korea’s Joseon period (1392 - 1910), delivery services became widespread among the upper class–especially /naengmyun/ (냉면) (cold noodles), a popular delicacy in the royal court.

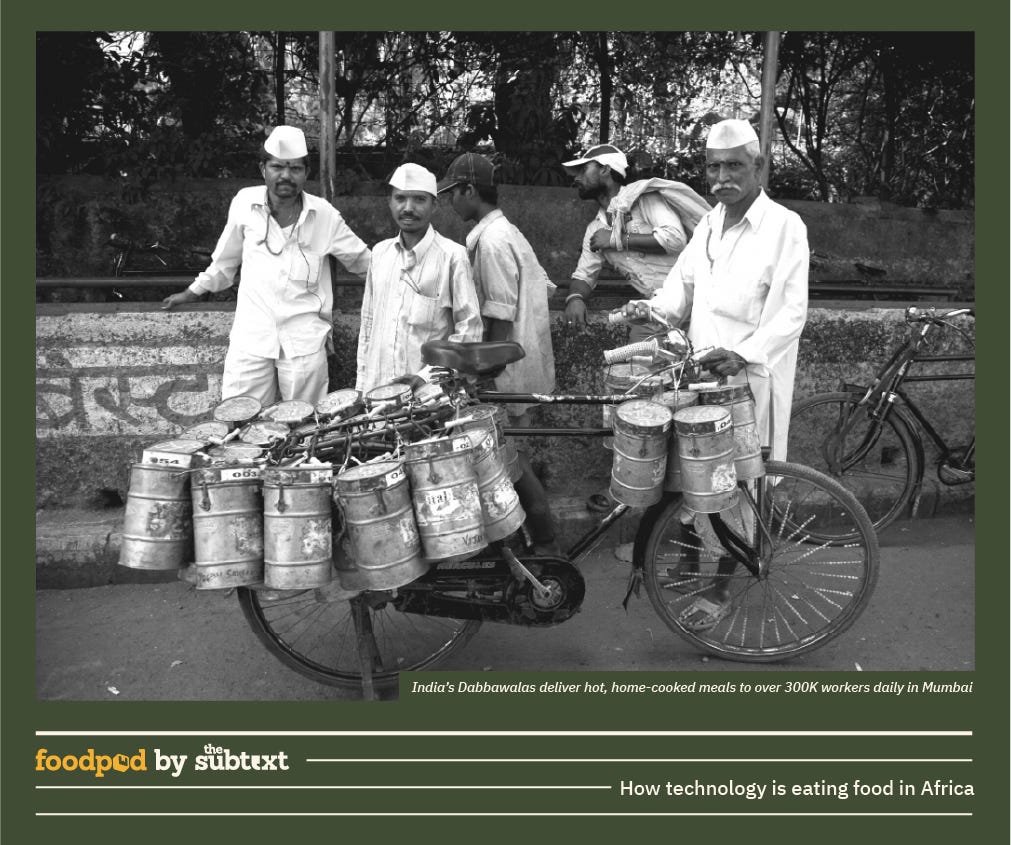

By the late 1800s, the dabbawala food delivery system sprang up on the streets of Mumbai to provide blue collar workers with hot, home-cooked meals. Under British rule, India experienced mass worker migration to urban centers: “Many of [them] moved to Mumbai, where they would leave for work extremely early in the morning and [...] often not have the time to go for lunch.” Dabbawala means “the one who carries the box”. The delivery men would pick up lunch boxes from different homes, transport them using bicycles and trains, then return the empty boxes afterwards. This system is still active today, serving up to 300,000 workers in 🇮🇳India’s most populous city.

After World War II, the British government trained its people to accept food delivery by shipping hot meals to families to keep up morale. In the US, it was the proliferation of television that did the trick. Consumers simply preferred sitting in front of the TV over going out to eat. Restaurants supported delivery out of economic necessity, often serving pizzas which grew popular after the war.

This pattern plays out repeatedly across cultures and centuries. Growing up, I remember food vendors hawking akara and pap on the streets of Benin City. My mother tells me women in our neighborhood would set up to cook and serve customers; a few portions made their way to the heads of relatives who carried them from street to street. It’s not clear exactly how this started, but across the country, millions of people still rely on these vendors to feed daily. Nigerians spend at least 20% of their food budget on meals consumed outside the home, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (2019).

It’s easy to see why. African markets tend to see a concentration of political/economic activity in a few cities. This drives mass migration from rural areas to urban centers, especially among people of working age who increasingly live online. Economic pressures delay family formation4, and urban realities—long commutes, unreliable power, limited space—make cooking inconvenient.

The result is a population of young, digitally-native city dwellers who lack the time, space, or will to cook their own food. Today, this group makes up approx. 3-4% of Nigeria’s urban population5, and, I’d say, is the primary customer base for food delivery services in this market (more in Chapter 3).

Online Food Delivery in Nigeria: 2012-?

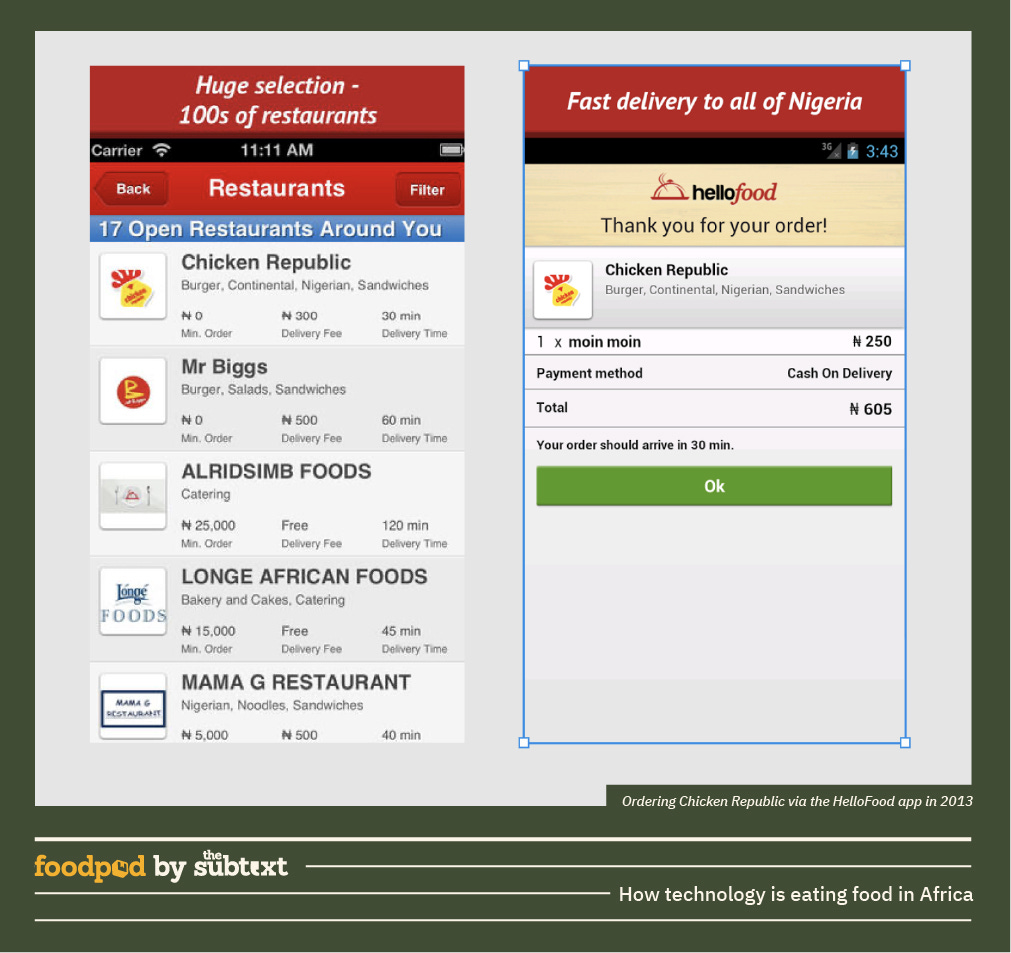

Rocket Internet launched HelloFood in November 2012, later rebranding it to Jumia Food. The e-commerce giant had to convince a skeptical population that it was safe, efficient, maybe even desirable to order digitally. This meant, for example: accepting cash payments (yuck), aggressive marketing campaigns, generous discounts, subsidized deliveries, and even pre-installing the app on Nokia and Samsung phones.

-

Even if its economics were poor, Jumia Food still served an important function for the mother-brand:

“Overall, [...] food delivery and on-demand service are an important growth engine for the platform, and key assets in terms of consumer acquisition and reengagement.”

That was Jeremy Hodara, Jumia co-founder/co-CEO during a 2021 earnings call. A little birdie from Jumia confirmed to me that the company ran cross-sell campaigns between its food delivery and e-commerce services. But while Jumia didn’t help carry packs of food, it was the rise of Amazon-style e-commerce that created the opening for food delivery in the first place.

Online takeaway sites emerged in the early 2010s, riding the smartphone penetration wave. Mobile phones were no longer just communications devices; they were now computers. Computers people used to send money, buy things, and exert their will on the world. foodpanda launched in 🇸🇬 Singapore (2012), and scaled rapidly across Asia and Eastern Europe; PedidosYa, Domicilios.com, and iFood pioneered food delivery across Latin America; and in the US, GrubHub, Seamless, and DoorDash battled for market dominance.

Meanwhile, in Africa, Konga and Jumia raised6 a total $759M to drive the adoption of e-commerce on the continent. Their war of attrition pulled forward many years’ worth of internet adoption. For better or worse, the latter attracted most of the capital, and–in addition to e-commerce–deployed it across multiple on-demand categories from food to travel, vehicles, and real estate.

Months before HelloFood, startups7 like LazyAppetite, founded by Deji Opoola and Nubi Kay, tried to get food delivery off the ground in Nigeria. From Nubi’s Medium page:

“[The e-commerce companies] paved the way for an online retail culture in Nigeria and it was not at a cheap price. In no time it became commonplace to buy electronics, books, and clothes online. This was the new trend we spotted before launching a food vertical. It was a no-brainer as it was all about creating an online marketplace where supply met demand [...] so we hit the road, pitched to over 50 restaurants and signed up 10 to launch LazyAppetite.com.”

LazyAppetite (later called EasyAppetite) earned a commission for referring customers to restaurants who handled their own deliveries. Early signs looked promising until a ban on motorcycles below 200c engine capacity by the government of the time:

“We had a huge [acceptance rate, but] didn’t find it easy delivering food since the bikes [used by] the restaurants were less than [the 200cc standard set] by the Lagos State Government. And for the customers, it wasn’t really their business how you got the food to them—you just [did].”

Restaurants were overwhelmed with requests but could not fulfill them. LazyAppetite put four vehicles on the road to start making deliveries. The company was eventually acqui-hired by mobility/logistics startup, MAX to launch MAXEats, their erstwhile food delivery service (September 2016).

I moved to Lagos in 2016 to start a new life as a technology reporter. Lunchtime at the office was often a question between Chicken Republic’s Chickwizz and the Double Chickwizz ($alary day 🤑). Chicken Republic leveraged its wide network of outlets to enable online ordering as early as 2015. Orders were placed via the website, while a partnership with ACE Logistics took care of deliveries and social media management.

The fast food chain–today, the largest in West Africa–is responsible for driving a large portion of the delivery adoption we’ve seen so far. I’d estimate that Chicken Republic alone accounts for up to 30% of Nigeria’s food delivery order volume, with major QSRs as a whole driving ~70%.

Word on the street is that Bolt Food exited the market because it lost the big QSRs to Chowdeck and Glovo89

For Jumia, it’s a slightly different story. Since its 2019 IPO, JMIA faced relentless pressure from investors to show sustainable growth. Public markets demand a path to profitability. Predictable profitability? 🧑🍳💋 Even better. Food delivery only made sense as a story about Jumia’s future potential. But in 2023, it was bleeding costs with no end in sight. The stock tanked 70% from its 2021 peak, as Wall Street was in no mood for money-losing experiments.

To stem the bleeding, incoming CEO Francis Dufay went on an aggressive cost-cutting drive: laying off nearly half the workforce, scaling back in underperforming markets, and yes, exiting food delivery altogether. Markets rewarded the discipline. Jumia’s market cap rose above $1B in July 2024 (for the first time since Feb 2021) before crashing back to $496M when they missed Q2 earnings–Nigerian food delivery consumers will be just fine.

-

By the time Jumia exited delivery (late 2023), the market had shifted beneath its feet. Persistent competition and a global pandemic were already altering consumer behavior.

Lockdowns forced people and businesses to rely on delivery services daily. And once you let that genie out of the bottle, there’s no putting it back. Even before the pandemic, OPay–a fintech ‘super app’ backed by Sequoia China & IDG Capital–entered the market and crashed prices to unsustainable levels. I heard about packs of food being sold for as low as ₦100 ($0.064), with free delivery 😲

Q: Why on earth was this worth it?

A: To drive habitual usage of OPay’s payments wallet.

Spoiler: it worked.

The party came to an end when the Lagos State government (again) banned motorcycles from most major roads in February 2022. Without the volumes from transportation, OPay’s bikes became an expensive hobby. By May, it sold off its fleet10 and focused on growing its offline financial services business. Like I said: Nigerian food delivery consumers will be just fine.

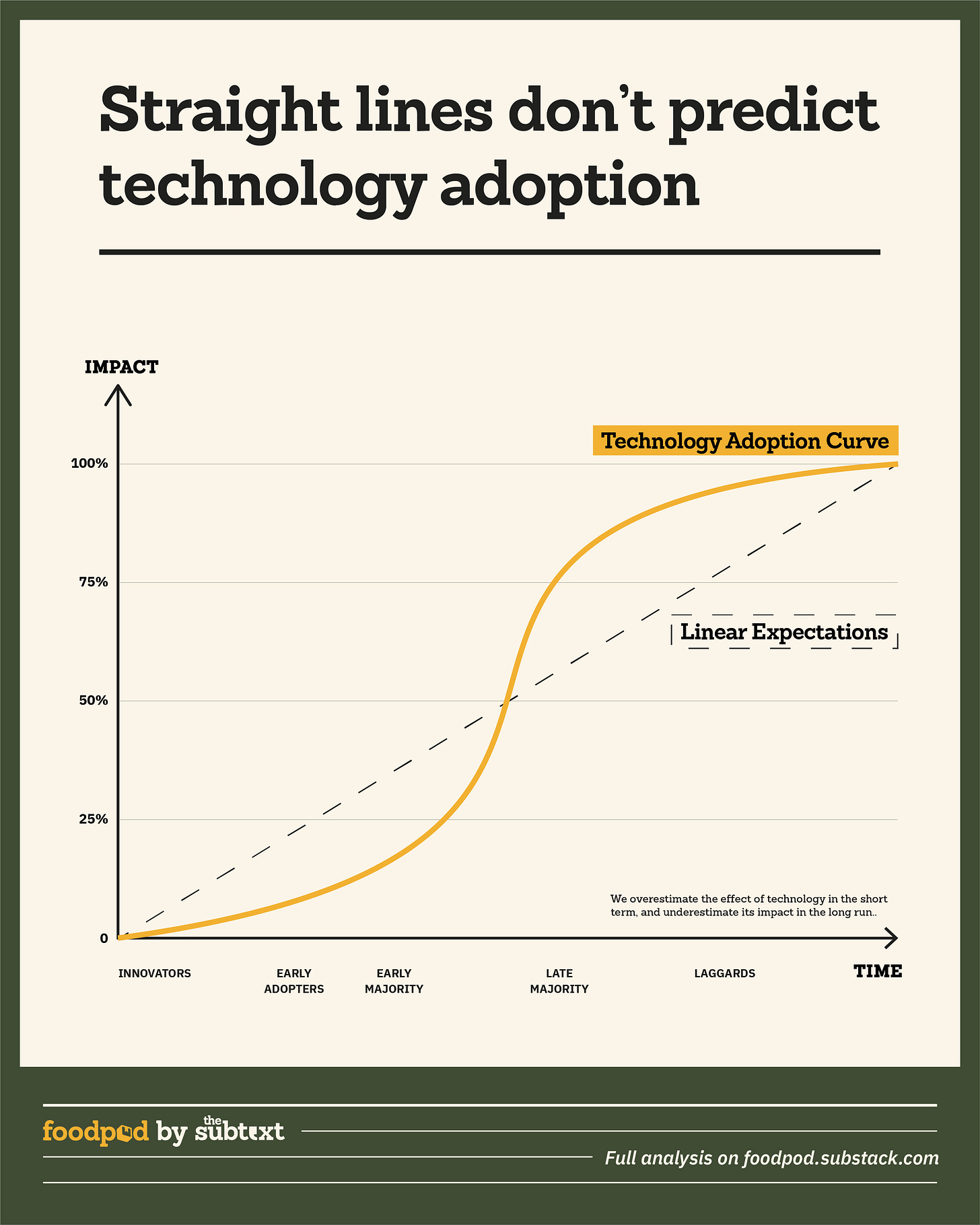

While they stumbled in food delivery, Jumia and OPay left behind a more mature ecosystem: new entrants don’t need to sweat as hard to educate the market. More importantly, the industry has built out critical enabling infrastructure in payments (cards, virtual bank accounts), logistics (motorbikes, trained riders, smartphones, financing), customer support, restaurant CRMs, etc. Jumia could have only wished for such luxuries.

The e-commerce giant had to offer cash on delivery to build customer trust; today, Chowdeck and Glovo can just assume we will pay for food digitally.

✨🫘 Magic Bean$

Of course, it is still early days. For all the talk of scale, Nigeria’s delivery platforms cumulatively serve at most a million active customers. There’s initial activity in tier 2 cities, but the vast majority of deliveries happen in Lagos, the economic capital (21M residents). According to Paystack, which processes payments for all the top delivery platforms, the Nigerian online food delivery market is valued at ₦50-70 billion (US$31-43 million) in GMV annually (Q1 2024). Indeed, it’s a long road ahead if the sector wants to reach the country’s 210M people.

Which brings me back to the question: can you build a business selling convenience in a market where money is more precious than time?

By conventional wisdom, economic downturns should devastate convenience services first, if not entirely. Yet in the past few years, Nigerian food delivery appears to have defied gravity.

While Jumia and Bolt crashed out of the market, Chowdeck and Glovo got to play ‘delivery’ on easy mode11. Hundreds of thousands of users now realised they wanted to order food online, and the new entrants only had to harvest the latent demand. At some point, though, it will become harder to acquire customers (if it hasn’t already 👀), and the game will become more about retention and monetisation.

If I’ve learned anything from the past nine years in technology, it is not to draw quick conclusions about non-consumption. Serve a real need, remove enough friction, find a viable business model, and new markets get created–seemingly overnight.

-

I can’t stop thinking of food delivery as ‘magic beans.’ In the popular English fairytale, Jack and the Beanstalk12, a young boy trades his family’s only cow for a bag of magic beans.

Frustrated by the foolishness, his mother threw them out the window, from where a giant beanstalk grew into the sky overnight.

Jack climbed the stem beyond the clouds, where he found a giant counting treasures: some gold coins, a hen that laid golden eggs, and a magical harp that played itself. That night, while the giant slept, Jack stole a few coins and escaped down the beanstalk. He returned two more times for the hen and the harp.

During the final trip, the giant woke up and chased Jack all the way down the beanstalk. “Mother! Mother!!” He called out, “hand me an ax!” then he chopped it down, causing the giant to fall to his death.

Jack and his mother lived comfortably ever after, feeding fat on the stolen treasures.

I can’t say that food delivery is a great business. The past decade shows the story is at least a little more complicated. What I can say, though, is that in the right hands, it could be a valuable asset.

Across times, cultures, and income levels, human beings allocate a ‘budget’ for convenience–money or time set aside to make life easier or more bearable (more on this in Chapter 3). How each person spends that budget, though, depends on their given time, culture, income level.

Food is fundamental, and this daily necessity drives habitual engagement with delivery apps. For delivery companies, this creates a faustian bargain; they trade off short term profits for a chance to serve more user needs–capture more ‘convenience spending’–over time. But users can be fickle.

So, perhaps the question is not whether you can build a large business doing delivery; perhaps it is about what you do once you’ve built one.

Like magic beans, food delivery may not seem lucrative at first glance. But for those who navigate the treacherous climb, there may yet be treasures at the top.

The value is not in delivery itself; it’s what it enables. The challenge, of course, is to find a golden hen before the market catches up.

—

Thank you for reading. Chapter 2 will examine food delivery in Nigeria through the lens of enabling infrastructure: what needs to exist for delivery to work at scale? Writing this one radicalized me–you don’t want to miss it. Hit subscribe so I can let you know when it’s out.

With love in my heart, and a fire in my belly,

-Osarumen

Edited by Ope Adedeji

Postscript: A Taxonomy of Food Delivery Concepts

Here are a few core concepts required for the rest of the series:

Delivery Platform vs. Aggregator – a delivery platform is any service that coordinates ordering and delivery, whether from a single vendor or multiple sources. An aggregator specifically connects customers with third-party vendors (restaurants, grocery stores, pharmacies, etc.), handling ordering, payments, and delivery logistics without needing to manage physical infrastructure. To illustrate: a virtual kitchen with an app that manages its own fleet is a food delivery platform, but not an aggregator.

Virtual Kitchen – A commercial kitchen space optimised and branded entirely or primarily for delivery. Traditional restaurants typically curate the eating experience, while the customer handles their own logistics. Virtual kitchens flip this dynamic, taking care of logistics and letting the customer curate their own eating experience. In this series, we distinguish between two main categories:

Cloud Kitchens, which are independently owned and operated

Dark Kitchens or Satellite Kitchens (owned by restaurants looking to expand their delivery footprint without opening full-service locations)

QSR/fast-food chain – a restaurant business optimized for high volume, standardized preparation, and quick service with limited menu options.

Rider/Driver/Courier – a person (or robot 🤖) who delivers food or groceries physically, regardless of transportation method. I will use the terms interchangeably depending on what each sentence desires.

Take Rate – the percentage of GMV (gross merchandise value, the total amount paid by the consumer) which is kept by the aggregator as a fee for their service. They may charge the customer or merchant additional fees but these are typically calculated after subtracting delivery fees and taxes.

Unit Economics – the direct revenues and costs associated with a specific business model expressed on a per-unit basis. For food delivery, this typically means the revenue, costs, and margin per-order, including restaurant commission, delivery fee, customer acquisition cost, and fulfillment expenses.

**Wherever I introduce a new concept not listed, I’ll include the definition in context.

Nigeria’s Cost Price Index (CPI) rose by 104.7% from 2021 to 2024, representing a 2x increase in the price of daily goods and services. The CPI is the primary measure of inflation, tracking the average price change over time for a representative basket of goods and services. In Nigeria, the CPI covers 960 items across 13 major categories, reflecting typical consumption patterns of Nigerian households.

This includes grocery delivery, which shares similar infra requirements but has distinct operational dynamics we’ll explore throughout the series. You should assume food & grocery delivery are interchangeable unless I say otherwise in the text.

Clarification: Jumia exited food delivery altogether, while Bolt still operates delivery services in other markets like Ghana, Kenya, and Poland.

Marriage data from cities across Africa show a continuous increase in the mean age of first marriage of women aged 18 - 50. In Lagos, the average age has increased from 19.7 years in 1996 to 25.0 years in 2023.

Estimate derived from a multi-step model combining metro population data (WorldPop, Macrotrends), age structure from the UN Population Division, formal employment rates from the World Bank and Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics; and income distribution from EFinA and Jobberman. Given sparse city-level data in Nigeria, this represents a best-fit projection based on available proxies. More to come in Chapter 3.

That is, as independent private companies in the 2010s. Jumia has raised an additional $896M since its 2019 IPO, while Konga was acquired by Zinox Group and merged with Yudala.

CityChops.com and NaijaEats.com launched in a similar period

A year later (August 2024), Chowdeck secured an exclusive delivery partnership with Chicken Republic for Lagos and Ibadan. By this time, the company was processing 40,000 daily deliveries, double the volume from April 2024. We will discuss the strategic implications in chapter three.

The data for this graphic was compiled from publicly available financial statements of QSRs owned by publicly listed companies in Nigeria. Financials for privately owned QSRs such as Mega Chicken and Sundry Foods (operators of Kilimanjaro, Pizza Grill) were unavailable, as they do not publish public reports. Additionally, companies not listed in Nigeria, such as Devyani International (India), which operates KFC and Pizza Hut, did not release Nigeria-specific financial data.

Mobility companies had varied responses to the 2020 Okada ban policy change. MAX exited Lagos and continued scaling its driver services platform across Nigeria and West Africa. OPay sold off half their fleet and pivoted from transportation to delivery as the primary use case. They would eventually focus on acquiring agents for their financial services business. Gokada, meanwhile, laid off most of its staff and pivoted to serve businesses, including Jumia Food. It filed for bankruptcy in 2024, four years after the tragic death of its founder.

As if.

Like all fairy tales, there are many versions of Jack and the Beanstalk; with additional details, different events & characters, etc. For this essay, I used Joseph Jacobs’ telling of the story (1890).